The Beijing government is in the midst of a three-year crackdown on the underground city below the capital that may house up to a million residents known as the “rat tribe”.

Tensions with the former Soviet Union during a border conflict in 1969 led to the creation of a vast, complicated network of tunnels built underneath Beijing in the 1970s in anticipation of a nuclear war. Covering 85 square kilometers and located eight to 18 meters beneath the surface, the underground tunnels were designed to accommodate six million people upon completion. With no war coming to pass and the tunnels long forgotten by city residents, newcomers to the capital have since moved into the tunnels as an alternative to paying the city’s high rents.

Without an official Beijing resident permit called a hukou, migrant workers have no access to low-cost government housing. That leaves the tunnels as one of the only affordable options.

Scheduled until December 2017, the government campaign will target the illegal use of underground space. Official estimates say there are 119,100 residents living in the underground tunnels that Chinese media reports describe as “risky”. Up until 2010, it was legal to live in one of these underground facilities.

The Beijing government say 3,125 facilities are being illegally used, including 932 civil air-defense constructions and another 2,192 regular residential basements.

Last year, Xinhua reported a fifth of the 7.7 million Beijing-based migrants live either at their workplace or underground. Beijing’s housing authority refuted this statistic, citing a government survey that totaled that number at 280,000. The issue came to public attention after local media reported a number of people using a manhole cover to access their homes in the sewer below, to which local authorities responded by sealing the manhole and evicting the residents inside.

Although a portion of it served as a tourist attraction from 2000 to 2008, the tunnels have been largely ignored by the government while they have gained attention in the media.

Photo of 21 year-old fashion design student Erry Qing by Sim Chi Yin.

Photographer Sim Chi Yin spent five years documenting the people known as “the rat tribe”, described as mostly young people “making the best of their lives” with ambitions to climb the social ladder.

“I think for some people there is true upward mobility but for many people the hukou system, whereby migrants can’t actually buy homes and settle down, is still a huge barrier to them building lives and families here,” said Sim.

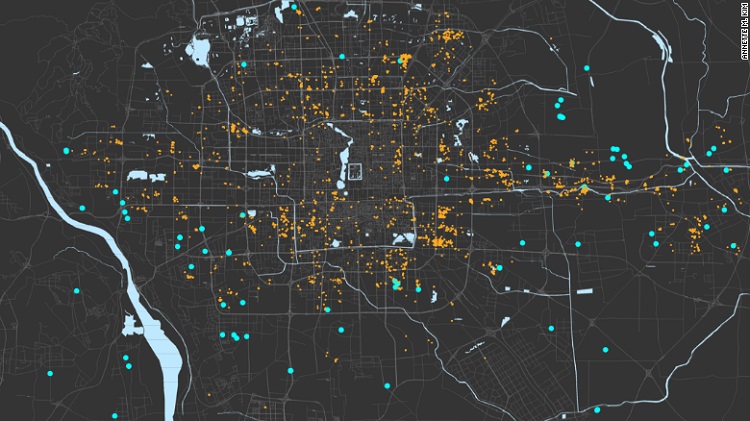

Professor Kim’s map in which orange dots represent underground residences, and blue dots represent affordable housing.

University of Southern California professor Annette Kim has mapped out much of the Beijing underground city by studying over 7,000 online classified ads in 2013. Kim found the average underground apartment to be 9.75 square meters, or 105 square feet, with an average rent of $70 a month.

Kim estimates that there are about one million people living underground who are deeply pragmatic, saying, “They would rather live underground than commute for a long time. It means that sometimes they could have two jobs.”

Beijing’s underground city was beginning to close down in 2011 when many of its entrances and access points were bricked up. Lonely Planet Beijing author David Eimer says it’s because of urban redevelopment. “Newer, bigger buildings require deeper foundations, so many of the tunnels have to be filled in for safety reasons,” said Eimer.

Photo of 19 year-old restaurant worker Su Fuzhou by Sim Chi Yin.

The extent of the network of tunnels is unclear, but is rumored to link Beijing’s central railway station with Tiananmen Square, the Temple of Heaven, the Forbidden City and the Western Hills. In keeping with the strategic use of underground facilities, the Beijing Metro was also designed to be able to move military personnel.

Built by 300,000 local conscripts including children, many of Beijing’s ancient walls that encircled the city were torn down and re-purposed as building material for the underground city. But even though this looks to be the end for Beijing underground city, another one looks poised to take its place. With real estate a prime commodity in the city, many real estate developers have been developing downwardsto make subterranean complexes, like the underground shopping malls in Dongcheng.