Chinese poet Gu Cheng’s letters released in Zhuhai

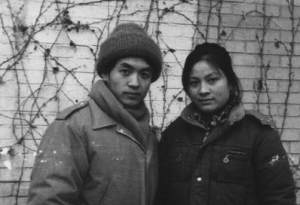

Posted: 01/28/2014 10:00 amAfter a documentary broadcast last month sparked increased interest in the poet, novelist and essayist Gu Cheng (1956-1993), letters he wrote when he was young were released to the media in Zhuhai on Jan. 25, Chinanews reports.

The author and critic Li Geng, who is 7 years Gu Cheng’s junior, released the letters sent to him between 1979 and 1981 when Li was still a teenager. They reveal Gu Cheng to have been full of self doubt but also to have a more genial personality than he is remembered for.

Even by the standards of poets who died young, Gu Cheng had an extraordinary life. The son of army poet Gu Gong, his family were sent off to Shandong to work on a pig farm during the Cultural Revolution. Gu Cheng claimed to have learnt poetry directly from nature and later became part of a group called the “misty” (朦胧) poets that were prominent in the late twentieth century.

On August 10, 1993, while employed as a Chinese lecturer at the University of Auckland, Gu Cheng attacked his wife Xie Ye with an axe before hanging himself. She died on the way to hospital.

Gu Cheng’s best known poem is the two-line piece “A Generation” which goes: “The dark night has given me dark eyes. But I use them to look for light.” This is thought to have encapsulated the experience of the generation that was young during the Cultural Revolution. It also forms the chorus of the song “Dark Eyes” by Shenzhen-based alternative singer Liang Ying.

A typical paragraph in the newly released letters goes: “You and I are quite alike, but in some ways are not alike. You seem to have more life in you than I do.” He later writes: “I hope to see your poetry, but I can’t give a critique. I don’t understand theory, or standards. I only understand emotions.” Gu Cheng then urges Li to please critique his work. They are also full of interesting tidbits such as the admission by Gu Cheng that he saw fellow misty poet Shu Ting as his soul mate and “like an older sister”.

Li thinks that Gu Cheng was a clinical depressive but lived in a society that was not yet enlightened about the issue. He also shared an important insight with a reporter from Chinanews. “In a short time, poetry has ceased to be part of real life in Chinese society. Pretty much nobody makes a living from poetry anymore. In a society that can’t produce great poets, poetry cannot go on producing a wealth of quality.”