There’s no doubt that living in China is like living life in overdrive; everything is faster, crazier, more unpredictable, and thus a whole lot more fun (if you can minimize the number of Bad China Days). We all have stories of crazy things we’ve seen, odd things our colleagues have done at work, or strange things our students have said. The sheer randomness of China is what lies at the heart of its attraction.

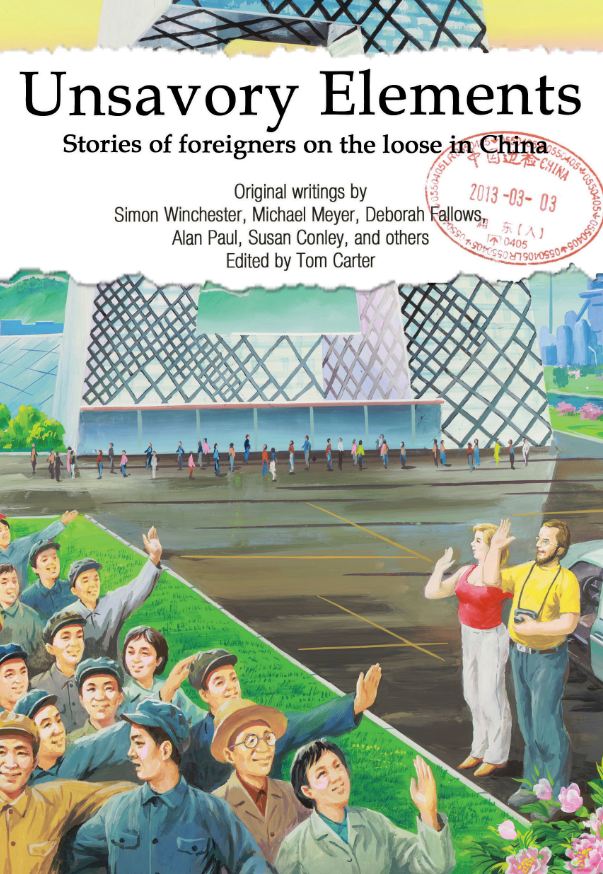

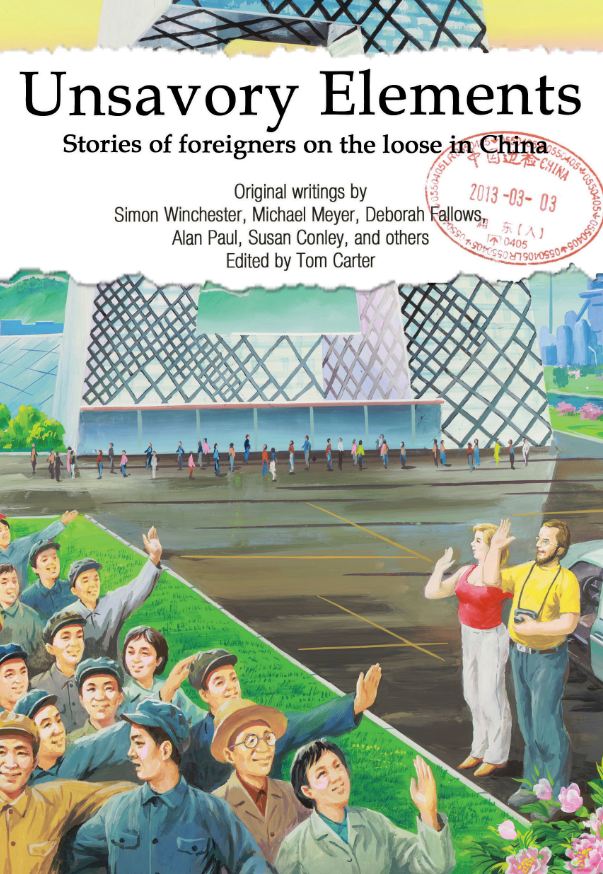

Tom Carter, an author now based in Shanghai, has decided to collect a number of these expat China adventures in a volume titled Unsavory Elements: Stories of Foreigners on the Loose in China. One of the contributors is Shenzhen’s very own Bruce Humes, who we profiled here on The Nanfang a few months ago.

Nobody on The Nanfang staff has read Unsavory Elements yet, but we plan to do it soon. In lieu of a review, we recently chatted with Carter by email regarding his anthology and the changing nature of expatdom in China.

You have an eclectic mix of writers: everyone from Simon Winchester (The River At The Center Of The World) and Peter Hessler (Country Driving) to Matthew Polly (American Shaolin) and Alan Paul (Big in China). How were you able to get so many notable people sign on for the project?

Probably because I conceived and approached this project as an actual fan of all the writers who appear in it, as opposed to an agent or publisher just looking to squeeze some money out of their book extracts, which unfortunately is how most anthologies come about.

I read the works of many of these authors for the first time during my 2-year backpacking sojourn across China – my pack was constantly filled to bursting with physical books. I respected them for inspiring generations of expats to follow in their footsteps and felt the moment had come to bring them all together, for the first time, on a single literary project to share all-new, never-before-told stories.

Even though I myself was also a published author, I didn’t know any of my contributors personally prior to this. I was pleasantly surprised by how accessible they were: most immediately wrote back, expressed an enthusiasm in contributing to this long-overdue showcase, and encouraged me to try to get it published.

I eventually took my proposal to Graham Earnshaw, an old China hand whom I had mad respect for for his decade-long walk – entirely by foot – across the length of China. His book The Great Walk of China is one of my favorites. Graham is also a publisher, he saw potential in my idea, and the rest is literary history.

The ‘expat adventures in China’ theme has been done before. What makes Unsavory Elements stand out?

Anthologies like Unsavory Elements are for those readers who enjoy dipping into short stories at their leisure. It offers a wide range of prose and a variety of perspectives that, in the spirit of our dissimilar backgrounds as expats, at times may contrast, and other times compliment each other.

I modeled the Unsavory theme after my backpacking days when I’d find myself lazing around some hostel in Dali or Dalian swapping travelers tales and debating issues with other backpackers from all over the world. Only an anthology can offer that kind of rich diversity.

The book is filled with expat adventures. Do you think as the country modernizes and becomes, in some ways, more western, that expats coming to China now and in the future will miss out on some of the crazier and more fun times?

As the editor, I was intent on making sure that all the stories in Unsavory Elements had a sort of timeless feel to them – experiences that occur just as commonly today as a decade ago – so that new and future expats could relate. And yet, modernization is a constant theme unintentionally running throughout the entire anthology; an undeniable variable that has not necessarily constrained the expat experience, but rather has taken the adventures to be had here to a new level.

A few examples from some of the more shocking essays in Unsavory: Susie Gordon’s Shanghai evening of ketamine, cocktails and KTV; Dominic Stevenson’s imprisonment for drug dealing; Bruce Humes getting knifed by a mugger in Shenzhen; Rudy Kong’s brawl with a bunch of off-duty policemen; and my own story about a boys-night-out at a brothel.

Of course the book is balanced out with an equal number of every-day accounts – a glimpse into our ordinary lives as foreigners living and working in China – but my point here is that China is as lawless today as it was last decade…just a bit more shiny is all.

China had a tremendous run up to the Olympic Games in 2008, but it seems interest in the country may be waning slightly. Do you believe there is still as much interest in China as there was a few years ago?

It’s true that many expats and entrepreneurs have been jumping ship lately – and making headlines for it – now that China’s economy has leveled off. In fact, in 2008 I myself left China for the very first time in four straight years because Beijing, where I had been based, was getting ridiculous with tourists and newcomers and journalists. I spent a year in Japan, and then another year in India. By the time I came back to China in 2010, I was admittedly happy to see the scene had calmed down.

But I can’t say I agree that interest in China has waned. Even though certain press agencies are pulling out their long-term correspondents, and even though some western businesses are retreating after realizing that there’s no more money to be gleaned, there’s more global attention on China today than ever before.

Granted, a lot of this is just a kind of cruel excitement by the western media who are waiting for the bubble to burst. And there’s also that contingent of China watchers who are predicting a new country-wide revolution if The Party doesn’t do something about the widening income gap. But the interest in China is still undeniably there.

Where / how can people in Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Dongguan buy the book?

Unsavory Elements has been a true grassroots project since inception. It was published in Shanghai by Earnshaw Books, launched at the Shanghai Literary Festival, the awesome cover art was donated by Plastered T-shirts in Beijing, and we are relying primarily on coverage in local expat scene ‘zines that I personally follow, such as The Nanfang, to help generate a buzz. In other words, the antithesis of a mass-market release; no agents, no publicists, no bought-and-paid for reviews.

But this also means that our China distribution will be limited to independent foreign language bookshops. Readers in Guangdong can pick up the physical book at Bookazine in Hong Kong, or just order it directly from Earnshaw Books – they’ll kuai di it out to you. And of course there’s always Kindle on Amazon. Needless to say, we are very much obliged for everyone’s support.

Miss Tan had a very simple dream: she wanted to leave China. When she married Mark, a UK national, she thought her dreams had come true. However, Mark had other plans.

Miss Tan had a very simple dream: she wanted to leave China. When she married Mark, a UK national, she thought her dreams had come true. However, Mark had other plans.

Opinion: Laowai is a Four Letter Word

Posted: 06/3/2014 12:00 pmIt’s thrown around by our colleagues, the jianbing seller, taxi driver, your students, and maybe even your friends. Even though it’s such a ubiquitous term, nobody seems to be quite sure what “laowai” really means. Should you feel good to be referred to that way, as a member of a prestigious club? Or should you be taken aback at being singled out as something different?

Some may say that “laowai” is a neutral term that doesn’t contain any inherent meaning other than “foreigner”. If there are any negative connotations in the word, they stem from the context in which the word is used. But this ignores the latent meaning of the word, shrouding it behind the banality of daily repetition that grinds its significance into unfeeling, bureaucratic indifference.

Taken literally, “laowai” written in Chinese is 老外 (lǎowài). Individually, its components are 老 (lǎo) meaning “old”, and 外 (wài), meaining “outside”. “Laowai” most definitely does not mean “foreigner” in Chinese; instead, that term is written as “外国人” (wàiguórén) which is made up of “外国” for “foreign” and “人” for “person”.

There is no English equivalent of “laowai” in English; this mostly stems from the fact that most English-speaking cultures don’t inherently view the world as being divided between themselves and everyone else (most, I said).

There may be some confusion to what “laowai” actually means due to its individual components. “Old” is universally regarded in Chinese culture as a sign of respect. If someone is called “Old Wang”, then the Wangster is a person of a dignified position, regardless of his age. With this same thinking, a “laowai” should be a position that is equally respected—something absolutely true if it wasn’t for the second half of the term, “outside”.

Family is the most important component of Chinese society. As a way to endear themselves to others, many Chinese will address strangers with family roles; for example, to call a fellow man a “哥们儿” (gēmenr) is to afford him the respect of not just a fellow brother, but an elder one. After family, the respect commanded by any one person starts to thin out the further away they are located from the family home: friends, business associates, co-workers, neighbors… until it becomes a question of geography.

Being an outsider is pretty much the lowest scale to occupy on the Chinese social hierarchy. You are not trusted; your customs and habits are strange and unfamiliar; you are the unknown that stands in contrast to the family circle; your existence is a contradiction to all that which is Chinese.

So when when taken together, “laowai” means “respectable outsider” and not the “Hey, old whitey!” that Lonely Planet tried to convince me of at a more naive stage of my stay here. One could take it as as a backhanded compliment if one enjoys masochism in their majesty, but the word “laowai” is basically a system of control to always alienate a foreigner. No matter how well you speak Chinese, no matter how much you pander, no matter how much you love China – you don’t belong.

Respectfully speaking, of course.

***

Editor’s note: If you’re still not convinced, we’ve found a very simple process to both confirm the opinions expressed here as well as to give yourself the social advantage anywhere in China. Please use responsibly.

Photo: iQiLu